Mesh Protocol Definition¶

Problem¶

There are very few ways to construct a peer to peer network in dynamic languages. Everyone who wants to make such a network needs to reinvent the wheel. For example, in Python, the only two such libraries either never made it out of beta, or were to connect to a cryptocurrency. There is certainly no way to communicate between these languages. This section will focus on how you can make a mesh (unorganized) network like the one in Bitcoin or Gnutella.

Design Goals¶

The network should be unorganized. This means that it’s very simple for connections to be added, and for routes to repair themselves in the event of obstruction. It also means that there is no central point of failure, nor overhead to maintaining a structure.

The network should also be as flexible as possible. It should be able to carry binary data and should have various flags to determine how a message is treated.

In languages that allow it, network nodes should be able to register custom callbacks, which can respond to incoming data in real time and act upon it as needed.

Most importantly, nodes should use features that are common across multiple languages.

And as an afterthought, nodes should be optimized for performance and data density where possible.

Node Construction¶

Now your node is ready to parse messages on the network, but it can’t yet connect. There are important elements it needs to store in order to interact with it correctly.

- A daemon thread or callback system which receives messages and incoming connections

- A routing table of peers with the IDs and corresponding connection objects

- A “waterfall list of recently received message IDs and timestamps

- A user-interactable queue of recently received messages

- A “protocol”, which contains:

- A sub-net flag

- An encryption method (or “Plaintext”)

- A way to obtain a SHA256-based ID of this

Connecting to the Network¶

This is where the protocol object becomes important.

When you connect to a node, each will send a message in the following format:

whisper

[your id]

[message id]

[timestamp]

handshake

[your id]

[your protocol id]

[your outward-facing address]

[json-ized list of supported compression methods, in order of preference]

When your node receives the corresponding message, the first thing your node does is compare their protocol ID against your own. If they do not match, your node shuts down the connection.

If they do match, your node adds them to your routing table

({ID: connection}), and makes a note of their outward facing

address and supported compression methods. Then your node sends a

standard response:

whisper

[your id]

[message id]

[timestamp]

peers

[json-ized copy of your routing table in format: [[addr, port], id]]

Upon receiving this message, your node attempts to connect to each given address. Now you’re connected to the network! But how do you process the incoming messages?

Message Propagation¶

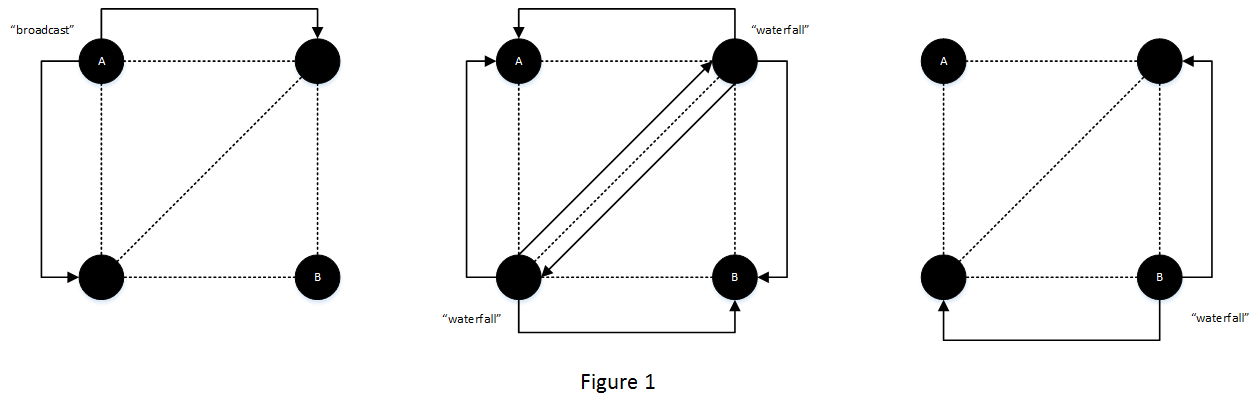

A message is initially broadcast with the broadcast flag. The

broadcasting node, as well as all receivers, store this message’s ID

and timestamp in their waterfall queue. The reciving nodes then

re-broadcast this message to each of their peers, but changing the

flag to waterfall.

A node which receives these waterfall packets goes through the following steps:

If the message ID is not in the node’s waterfall queue, continue and add it to the waterfall queue

Perform cleanup on the waterfall queue

- Remove all possible duplicates (sending may be done in multiple threads, which may result in duplicate copies)

- Remove all IDs with a timestamp more than 1 minute ago

Re-broadcast this message to all peers (optionally excluding the one you received it from)

Renegotiating a Connection¶

It may be that at some point a message fails to decompress on your

end. If this occurs, you have an easy solution, your node can send a

renegotiate message. This flag is used to indicate that a message

should never be presented to the user, and is only used for

connection management. At this time there are two possible

operations.

The compression subflag will allow your node to renegotiate your

compression methods. A message using this subflag should be

constructed like so:

renegotiate

[your id]

[message id]

[timestamp]

compression

[json-ized list of desired compression methods, in order of preference]

Your peer will respond with the same message, excluding any methods they do not support. If this list is different than the one you sent, you reply, trimming the list of methods your node does not support. This process is repeated until the two agree upon a list.

Your node may also send a resend subflag, which requests your

peer to resend the previous whisper or broadcast. This is

structured like so:

renegotiate

[your id]

[message id]

[timestamp]

resend

Peer Requests¶

If you want to privately reply to a message where you are not directly connected to a sender, the following method can be used:

First, your node broadcasts a message to the network containing the

request subflag. This is constructed as follows:

broadcast

[your id]

[message id]

[timestamp]

request

[a unique, base_58 id you assign]

[the id of the desired peer]

Then your node places this in a dictionary so your node can watch for when this is responded to. A peer who gets this will reply:

broadcast

[their id]

[message id]

[timestamp]

response

[the id you assigned]

[address of desired peer in format: [[addr, port], id] ]

When this is received, your node removes the request from your dictionary, makes a connection to the given address, and sends the message.

Another use of this mechanism is to request a copy of your peers’ routing tables. To do this, your node may send a message structured like so:

whisper

[your id]

[message id]

[timestamp]

request

*

A node who receives this will respond exactly as they do after a

successful handshake. Note that while it is technically valid to send

this request as a broadcast, it is generally discouraged.

Potential Flaws¶

This network shcema has an immediately obvious shortcoming.

In a worst case scenario, every node will receive a given message \(n-1\) times, and each message will generate \(n * (n-1)\) total broadcasts, where n is the number of connected nodes. This number can be arrived at by thinking of the network serially. If you have four nodes on a network, each connected to the other three, it will proceed roughly as follows.

Node A will send to B, C, and D. Node B will receive this message and send to A, C, and D. Node C will receive the same message and send to A, B, and D. Node D will relay to A, B, and C. This makes 12 total messages, or \(n * (n-1)\).

In most larger cases this will not happen, as a given node will not be connected to everyone else. But in smaller networks this will be common, and in well-connected networks this could slow things down. This calls for optimization, and will need to be explored.

For instance, not propagating to a peer you receive a message from reduces the number of total broadcasts to \((n-1)^2\). Using the same example:

Node A will send to B, C, and D. Node B will receive this message and send to C and D. Node C will receive the same message and send to B and D. Node D will relay to B and C. This makes 9 total messages, or \((n-1)^2\).

Limiting your number of connections can bring this down to \(min(MaxConns, n-1) * (n-1)\).